Knowing how much rain falls on a location is key to determining if any unfilled thirst remains unfilled at that particular location. Unfortunately, however, knowing actual rainfall amounts has always been a very difficult task.

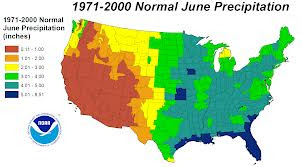

Typical Precipitation Map

Resolution of data that makeup such a map is, at best, around 50 miles and is possibly as high as 100-200 miles. This data is gathered from rain gauges installed every 50, 100 or larger distances apart.

We are, however, very well aware that rainfall amounts are not usually similar or identical over a 50 mile or a 100 mile or a 200 mile square of area.

Using rainfall data from this map can lead to incorrect conclusions: thirst experienced by some farms can be overlooked, or, some farms that don't experience thirst can be targeted for additional water supply. In either case, resources expended to deliver water (safe for irrigation) will end up being misspent.

Radar Maps

Doppler radar have better resolution that do rainfall data maps.

However, the installed base of Doppler radar sites are predominantly around major cities and population centers. Doppler radar, thus, provides us with high resolution rainfall maps in and around cities.

Farms or other remote agricultural locations have few of these radars and thus assessing their thirst is a problematic task

Towers (for mobile phones) may hold the answer!

For cell phones to work, microwave transmissions are relayed between individual towers.

These microwave signals, between towers, are transmitted at a known constant strength that allows for signal decay over distance and for known weather conditions that might reasonably be anticipated. For a particular weather condition, the rate at which this signal falls off (or deteriorates) can be predicted for any set of towers.

When liquid water is in the air (i.e. it is raining), however, the signal between towers drops (is weaker) because a part of the signal is reflected off raindrops and does not make it to the next tower.

Depending upon terrain, towers can be just 1-2 miles apart.

The Netherlands Experiment

Netherlands, the country, has just 32 rain gauges, but about 8,000 mobile phone towers.

An algorithm has been developed that measures differences between normal (no rain) signal strength and signal strength when it rains.

An experiment was run, in September 2011, to see how well signal monitoring could measure actual rainfall amounts.

This test, conducted with data from just 2400 cell towers, mapped rainfall amounts very close to the measurements from a combination of radar and rain gauges.

Thirst in the Developing and Underdeveloped worlds As cell phones, and the towers that enable them, have become commonplace all over the developing and underdeveloped world, its a simpler step to use cell phone signals to measure and predict rainfall amounts in real time. The traditional alternative, involving radar and rain gauges, may not be necessary any more.

This post was inspired by an article in The New Scientist magazine

Typical Precipitation Map

|

| Source - climatecentral.org |

We are, however, very well aware that rainfall amounts are not usually similar or identical over a 50 mile or a 100 mile or a 200 mile square of area.

Using rainfall data from this map can lead to incorrect conclusions: thirst experienced by some farms can be overlooked, or, some farms that don't experience thirst can be targeted for additional water supply. In either case, resources expended to deliver water (safe for irrigation) will end up being misspent.

Radar Maps

|

| Source - weathercentral.com |

However, the installed base of Doppler radar sites are predominantly around major cities and population centers. Doppler radar, thus, provides us with high resolution rainfall maps in and around cities.

Farms or other remote agricultural locations have few of these radars and thus assessing their thirst is a problematic task

Towers (for mobile phones) may hold the answer!

For cell phones to work, microwave transmissions are relayed between individual towers.

These microwave signals, between towers, are transmitted at a known constant strength that allows for signal decay over distance and for known weather conditions that might reasonably be anticipated. For a particular weather condition, the rate at which this signal falls off (or deteriorates) can be predicted for any set of towers.

When liquid water is in the air (i.e. it is raining), however, the signal between towers drops (is weaker) because a part of the signal is reflected off raindrops and does not make it to the next tower.

Depending upon terrain, towers can be just 1-2 miles apart.

The Netherlands Experiment

|

| Source - lonelyplanet.com |

An algorithm has been developed that measures differences between normal (no rain) signal strength and signal strength when it rains.

An experiment was run, in September 2011, to see how well signal monitoring could measure actual rainfall amounts.

This test, conducted with data from just 2400 cell towers, mapped rainfall amounts very close to the measurements from a combination of radar and rain gauges.

Thirst in the Developing and Underdeveloped worlds As cell phones, and the towers that enable them, have become commonplace all over the developing and underdeveloped world, its a simpler step to use cell phone signals to measure and predict rainfall amounts in real time. The traditional alternative, involving radar and rain gauges, may not be necessary any more.

This post was inspired by an article in The New Scientist magazine